HAMED SINNO on THIS ARAB is QUEER pubblished in 2022 by SAQI books said:

To sing with the intention of being heard is to declare the following:

- Your body is larger then society. Society is language. To sing is to insist that your body matters; that it is greater then language; that it can do things outside of language, and demand that the world recognize it as a carrier of meaning and value in its own right. That you are greater that what we have conceptualized into language.

- You are still breathing. To sing is to make a spectacle of breath, of drawing-in life force, of taking from the shared, of survival. This is particularly transgressive for minority bodies that the world is hell-bent on disappearing, regulating or destroying. You sing to let them know they haven’t killed you yet.

- You demand that existence be more then survival. When you sing you are not just making a spectacle of breath; you are making a spectacle of turning air into more then breath, into more then meaning. It is a celebration of the body: look at what this abject flesh case can do with air, look at how much space you can take up with it. Behold the inner workings of this meat they try to control. Listen to the spit, the voice breaks, the tongue flapping, the lungs, the mucus. „Here it is the inside of my body. It is glorious.“

and i say, it is beautiful, enormous. if you ever thought of singing – or wanted or tried or dreamed about it…… DO IT! it will be an amazing contribution to your life and to society! queerlove,lila

NEW WAYS with ONE OWN ROOM FOR EXPERITHEATER ZüRICH

https://akutmag.ch/der-bedrohte-dachstuhl-vom-experi-theater-zuerich/

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zVJgy-uGyw4

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=tRhoaRlyeq8

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Not a red rose or a satin heart.

I give you an onion.

It is a moon wrapped in brown paper.

It promises light

like the careful undressing of love.

Here.

It will blind you with tears

like a lover.

It will make your reflection

a wobbling photo of grief.

I am trying to be truthful.

Not a cute card or a kissogram.

I give you an onion.

Its fierce kiss will stay on your lips,

possessive and faithful

as we are,

for as long as we are.

Take it.

Its platinum loops shrink to a wedding-ring,

if you like.

Lethal.

Its scent will cling to your fingers,

cling to your knife.

Carol Ann Duffy

————————

As Nina Simone once said: „it is our duty as artists to reflect the times“.

————————-

Chamamanda Ngozi I'm a storyteller. And I would like to tell you a few personal stories about what I like to call "the danger of the single story." I grew up on a university campus in eastern Nigeria. My mother says that I started reading at the age of two, although I think four is probably close to the truth. So I was an early reader, and what I read were British and American children's books. I was also an early writer, and when I began to write, at about the age of seven, stories in pencil with crayon illustrations that my poor mother was obligated to read, I wrote exactly the kinds of stories I was reading: All my characters were white and blue-eyed, they played in the snow, they ate apples, and they talked a lot about the weather, how lovely it was that the sun had come out. Now, this despite the fact that I lived in Nigeria. I had never been outside Nigeria. We didn't have snow, we ate mangoes, and we never talked about the weather, because there was no need to. My characters also drank a lot of ginger beer, because the characters in the British books I read drank ginger beer. Never mind that I had no idea what ginger beer was. And for many years afterwards, I would have a desperate desire to taste ginger beer. But that is another story. What this demonstrates, I think, is how impressionable and vulnerable we are in the face of a story, particularly as children. Because all I had read were books in which characters were foreign, I had become convinced that books by their very nature had to have foreigners in them and had to be about things with which I could not personally identify. Now, things changed when I discovered African books. There weren't many of them available, and they weren't quite as easy to find as the foreign books. But because of writers like Chinua Achebe and Camara Laye, I went through a mental shift in my perception of literature. I realized that people like me, girls with skin the color of chocolate, whose kinky hair could not form ponytails, could also exist in literature. I started to write about things I recognized. Now, I loved those American and British books I read. They stirred my imagination. They opened up new worlds for me. But the unintended consequence was that I did not know that people like me could exist in literature. So what the discovery of African writers did for me was this: It saved me from having a single story of what books are. I come from a conventional, middle-class Nigerian family. My father was a professor. My mother was an administrator. And so we had, as was the norm, live-in domestic help, who would often come from nearby rural villages. So, the year I turned eight, we got a new house boy. His name was Fide. The only thing my mother told us about him was that his family was very poor. My mother sent yams and rice, and our old clothes, to his family. And when I didn't finish my dinner, my mother would say, "Finish your food! Don't you know? People like Fide's family have nothing." So I felt enormous pity for Fide's family. Then one Saturday, we went to his village to visit, and his mother showed us a beautifully patterned basket made of dyed raffia that his brother had made. I was startled. It had not occurred to me that anybody in his family could actually make something. All I had heard about them was how poor they were, so that it had become impossible for me to see them as anything else but poor. Their poverty was my single story of them. Years later, I thought about this when I left Nigeria to go to university in the United States. I was 19. My American roommate was shocked by me. She asked where I had learned to speak English so well, and was confused when I said that Nigeria happened to have English as its official language. She asked if she could listen to what she called my "tribal music," and was consequently very disappointed when I produced my tape of Mariah Carey. She assumed that I did not know how to use a stove. What struck me was this: She had felt sorry for me even before she saw me. Her default position toward me, as an African, was a kind of patronizing, well-meaning pity. My roommate had a single story of Africa: a single story of catastrophe. In this single story, there was no possibility of Africans being similar to her in any way, no possibility of feelings more complex than pity, no possibility of a connection as human equals. I must say that before I went to the U.S., I didn't consciously identify as African. But in the U.S., whenever Africa came up, people turned to me. Never mind that I knew nothing about places like Namibia. But I did come to embrace this new identity, and in many ways I think of myself now as African. Although I still get quite irritable when Africa is referred to as a country, the most recent example being my otherwise wonderful flight from Lagos two days ago, in which there was an announcement on the Virgin flight about the charity work in "India, Africa and other countries." So, after I had spent some years in the U.S. as an African, I began to understand my roommate's response to me. If I had not grown up in Nigeria, and if all I knew about Africa were from popular images, I too would think that Africa was a place of beautiful landscapes, beautiful animals, and incomprehensible people, fighting senseless wars, dying of poverty and AIDS, unable to speak for themselves and waiting to be saved by a kind, white foreigner. I would see Africans in the same way that I, as a child, had seen Fide's family. This single story of Africa ultimately comes, I think, from Western literature. Now, here is a quote from the writing of a London merchant called John Locke, who sailed to west Africa in 1561 and kept a fascinating account of his voyage. After referring to the black Africans as "beasts who have no houses," he writes, "They are also people without heads, having their mouth and eyes in their breasts." Now, I've laughed every time I've read this. And one must admire the imagination of John Locke. But what is important about his writing is that it represents the beginning of a tradition of telling African stories in the West: A tradition of Sub-Saharan Africa as a place of negatives, of difference, of darkness, of people who, in the words of the wonderful poet Rudyard Kipling, are "half devil, half child." And so, I began to realize that my American roommate must have throughout her life seen and heard different versions of this single story, as had a professor, who once told me that my novel was not "authentically African." Now, I was quite willing to contend that there were a number of things wrong with the novel, that it had failed in a number of places, but I had not quite imagined that it had failed at achieving something called African authenticity. In fact, I did not know what African authenticity was. The professor told me that my characters were too much like him, an educated and middle-class man. My characters drove cars. They were not starving. Therefore they were not authentically African. But I must quickly add that I too am just as guilty in the question of the single story. A few years ago, I visited Mexico from the U.S. The political climate in the U.S. at the time was tense, and there were debates going on about immigration. And, as often happens in America, immigration became synonymous with Mexicans. There were endless stories of Mexicans as people who were fleecing the healthcare system, sneaking across the border, being arrested at the border, that sort of thing. I remember walking around on my first day in Guadalajara, watching the people going to work, rolling up tortillas in the marketplace, smoking, laughing. I remember first feeling slight surprise. And then, I was overwhelmed with shame. I realized that I had been so immersed in the media coverage of Mexicans that they had become one thing in my mind, the abject immigrant. I had bought into the single story of Mexicans and I could not have been more ashamed of myself. So that is how to create a single story, show a people as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again, and that is what they become. It is impossible to talk about the single story without talking about power. There is a word, an Igbo word, that I think about whenever I think about the power structures of the world, and it is "nkali." It's a noun that loosely translates to "to be greater than another." Like our economic and political worlds, stories too are defined by the principle of nkali: How they are told, who tells them, when they're told, how many stories are told, are really dependent on power. Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person. The Palestinian poet Mourid Barghouti writes that if you want to dispossess a people, the simplest way to do it is to tell their story and to start with, "secondly." Start the story with the arrows of the Native Americans, and not with the arrival of the British, and you have an entirely different story. Start the story with the failure of the African state, and not with the colonial creation of the African state, and you have an entirely different story. I recently spoke at a university where a student told me that it was such a shame that Nigerian men were physical abusers like the father character in my novel. I told him that I had just read a novel called "American Psycho" -- and that it was such a shame that young Americans were serial murderers. Now, obviously I said this in a fit of mild irritation. But it would never have occurred to me to think that just because I had read a novel in which a character was a serial killer that he was somehow representative of all Americans. This is not because I am a better person than that student, but because of America's cultural and economic power, I had many stories of America. I had read Tyler and Updike and Steinbeck and Gaitskill. I did not have a single story of America. When I learned, some years ago, that writers were expected to have had really unhappy childhoods to be successful, I began to think about how I could invent horrible things my parents had done to me. But the truth is that I had a very happy childhood, full of laughter and love, in a very close-knit family. But I also had grandfathers who died in refugee camps. My cousin Polle died because he could not get adequate healthcare. One of my closest friends, Okoloma, died in a plane crash because our fire trucks did not have water. I grew up under repressive military governments that devalued education, so that sometimes, my parents were not paid their salaries. And so, as a child, I saw jam disappear from the breakfast table, then margarine disappeared, then bread became too expensive, then milk became rationed. And most of all, a kind of normalized political fear invaded our lives. All of these stories make me who I am. But to insist on only these negative stories is to flatten my experience and to overlook the many other stories that formed me. The single story creates stereotypes, and the problem with stereotypes is not that they are untrue, but that they are incomplete. They make one story become the only story. Of course, Africa is a continent full of catastrophes: There are immense ones, such as the horrific rapes in Congo and depressing ones, such as the fact that 5,000 people apply for one job vacancy in Nigeria. But there are other stories that are not about catastrophe, and it is very important, it is just as important, to talk about them. I've always felt that it is impossible to engage properly with a place or a person without engaging with all of the stories of that place and that person. The consequence of the single story is this: It robs people of dignity. It makes our recognition of our equal humanity difficult. It emphasizes how we are different rather than how we are similar. So what if before my Mexican trip, I had followed the immigration debate from both sides, the U.S. and the Mexican? What if my mother had told us that Fide's family was poor and hardworking? What if we had an African television network that broadcast diverse African stories all over the world? What the Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe calls "a balance of stories." What if my roommate knew about my Nigerian publisher, Muhtar Bakare, a remarkable man who left his job in a bank to follow his dream and start a publishing house? Now, the conventional wisdom was that Nigerians don't read literature. He disagreed. He felt that people who could read, would read, if you made literature affordable and available to them. Shortly after he published my first novel, I went to a TV station in Lagos to do an interview, and a woman who worked there as a messenger came up to me and said, "I really liked your novel. I didn't like the ending. Now, you must write a sequel, and this is what will happen ..." And she went on to tell me what to write in the sequel. I was not only charmed, I was very moved. Here was a woman, part of the ordinary masses of Nigerians, who were not supposed to be readers. She had not only read the book, but she had taken ownership of it and felt justified in telling me what to write in the sequel. Now, what if my roommate knew about my friend Funmi Iyanda, a fearless woman who hosts a TV show in Lagos, and is determined to tell the stories that we prefer to forget? What if my roommate knew about the heart procedure that was performed in the Lagos hospital last week? What if my roommate knew about contemporary Nigerian music, talented people singing in English and Pidgin, and Igbo and Yoruba and Ijo, mixing influences from Jay-Z to Fela to Bob Marley to their grandfathers. What if my roommate knew about the female lawyer who recently went to court in Nigeria to challenge a ridiculous law that required women to get their husband's consent before renewing their passports? What if my roommate knew about Nollywood, full of innovative people making films despite great technical odds, films so popular that they really are the best example of Nigerians consuming what they produce? What if my roommate knew about my wonderfully ambitious hair braider, who has just started her own business selling hair extensions? Or about the millions of other Nigerians who start businesses and sometimes fail, but continue to nurse ambition? Every time I am home I am confronted with the usual sources of irritation for most Nigerians: our failed infrastructure, our failed government, but also by the incredible resilience of people who thrive despite the government, rather than because of it. I teach writing workshops in Lagos every summer, and it is amazing to me how many people apply, how many people are eager to write, to tell stories. My Nigerian publisher and I have just started a non-profit called Farafina Trust, and we have big dreams of building libraries and refurbishing libraries that already exist and providing books for state schools that don't have anything in their libraries, and also of organizing lots and lots of workshops, in reading and writing, for all the people who are eager to tell our many stories. Stories matter. Many stories matter. Stories have been used to dispossess and to malign, but stories can also be used to empower and to humanize. Stories can break the dignity of a people, but stories can also repair that broken dignity. The American writer Alice Walker wrote this about her Southern relatives who had moved to the North. She introduced them to a book about the Southern life that they had left behind. "They sat around, reading the book themselves, listening to me read the book, and a kind of paradise was regained." I would like to end with this thought: That when we reject the single story, when we realize that there is never a single story about any place, we regain a kind of paradise. Thank you.

FEBRUARY 2017

Untitled Poem, Joyce Mansour

Never tell your dream

To the one who doesn’t love you

The hostile ear is dried up

The bitter mouth maligns

Hatred vomits the sand in the hourglass

Faster always faster

The betrayed night aborts

A passion in the present already passed

And fear only augments

The rage of the caiman

The size of the cancer

Bury your dreams in the bags under your eyes

They will be safe from envy

They will be safe from the adage

That the African babbles

And all the old are wise

[Translated from the French by Gaelle Raphael]

JANUARY 2017

it has been a long while since i wrote on my website. confused, unfocused, lazy, out of time. then less confused, more focused and definitively still lazy, now i write. in one sentence i want to thank everyone who supported in different ways, means and moments my music project since i started in january 2014. in a second sentence i want to thank all the amazing places i visited, the landscapes i’ve seen, all the people i met, got to know, heard of, read about, that with their lives, wishes, ideas, work, simply by being who they are have moved and inspired me to sing. over and again and then another song.

lately i realized that i often live in an inner and outer world of questions. although those questions more often then not irritate me and leave me puzzled, i try not to disregard them. i’m confident that finally the effort to try to answer them brings me to stand for inner convictions, ideals, utopia, perseverance, for what i understand as making sense out of what happens, as being part of, as activism, as patience.

knowing that all those questions, ideals, inner convictions, patience are in process helps me to appreciate them as they keep my mind awake and in exchange with others, as they accompany me to acknowledge my limits OR overcome them and also, i see as they take place in different forms in the course of my life and shape it.

the music i do is part of that process. something that touched me in the first place, something that after i try to work out through lyrics and melodies, something that later i long to share by singing. with the live performance i try to create a moment of connection with the people that find in it inputs, inspiartion, common ground or whatever it is that we recognize when we listen to a song and get caught with it in a flow of feelings.

… i had to smile then laughed when the day after updating this webpage i found this note on my teabag:

VIENNA

october, 2014

it has been a wonderful experience to be on tour for a week in vienna. it felt a bit like being on the road except i didn’t have my camper-van -as it used to be… much better, i was hosted in a wonderful wg with loads of people coming in and out…each morning i met someone new. and lovely maren rahmann!!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZFLU0TsImlg

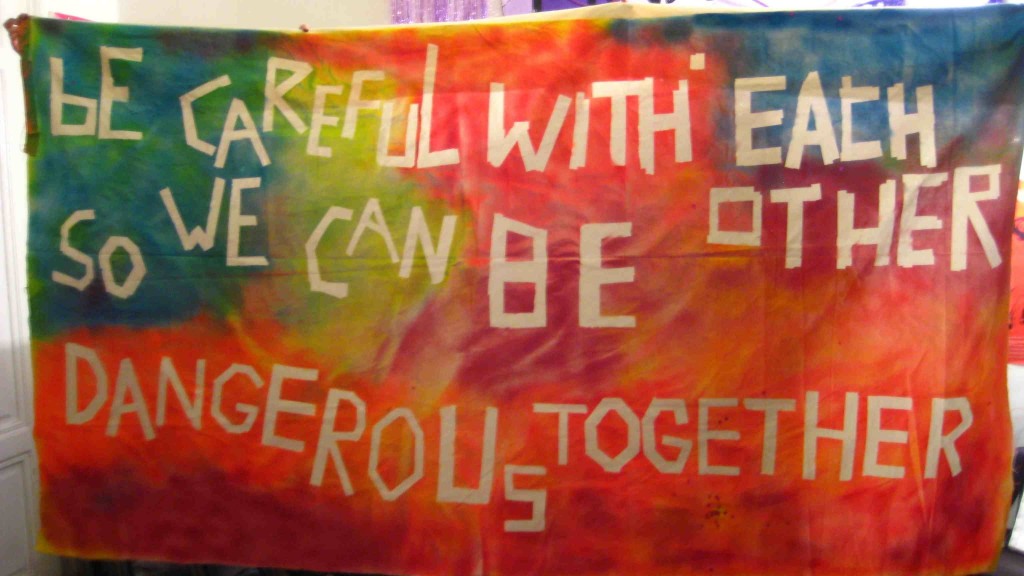

we talked together about music, possibilities to perform, women that moved society with their work and about second-hand guitar shops. i loved it. the evenings were full of music – i felt the urge to be heard and met loads of ears and hearts. that made me real happy! elektro gönnaaa and café7stern: thanks for your warm welcome – looking forward to perform again at your venues. the fantastic frauencafé where i felt like home among the queer community – LET’S BE CAREFUL WITH EACH OTHER TO BE DANGEROUS TOGETHER!! YES, LET’S DO THAT!

HELSINKI-KLUB, zürich

September 2014

nothing has to be perfect but some things shall only come from the heart! like last night at helsinki – warm and cosy. a whole living room of people and music for leonard cohen 80st birthday! real lovely interpretations of cohen’s work. HAPPY BIRTHDAY MASTER!!!

HAMBURG SÜD & BERLIN

June 2014

dear dear, only a few days away from home to find out that there is nothing like the northern clouds to keep me steady and out of my mind. Half sky, half ground. like whales. so grand, so sexy, so tender! they melt, mate and let go, change shape and position at such pace that it is hard for me to keep tracks of their queerful games. the wind blows and they show off their transforming skills. those clouds give no chance to my pragmatic thoughts: „i have worries!!!!“….“anything is possible“ they answer – „easy to say it from up there“ i say. „no time to be attached if not to oneself, the imaginary harbour!“ and then they carry on, fly low. everything in between -half sky, half ground- moves on.

ZIEGEL OH LAC, ROTE FABRIK

may 2014

„It was just one of those nights

Just one of those fabulous flights

A trip to the moon on gossamer wings…“

and i didn’t land yet but i feel the ground is nearer.

it has been very interesting to feel what it means to me to sing in a big venue like the one at „ziieschitgmusig“, rote fabrik and thanks to alex, debora and all the friends who came around to support me (thank you hey!) i had the chance to try it out and didn’t faint, managed to sing my set to the end.

but the most wonderful thing of that night has been wallis bird and band: sparkles above on lava land. i loved it and not only me, everyone from the audience was covered in glow as they left the venue and coloured their way home. and it got even better in the after-hours when the team of ziegel oh lac gathered together in the back room and wallis and aidan sang and played us into the morning light… well, there is loads of great music running in those people’s veins and melodies and the way they share it all!!! wow! for a moment i felt i wasn’t a stranger in life. oh, it felt so good!! then „the bells of the morning“ took them over the alps to „tell that story one more time“. spread it. love is music-al.

i’m now slowly arriving back to the queer underground world – also a wonderful cosy place for me to be off-pride in love – though i’ll miss you. THANK YOU BIRDS! WISH YOU A GREAT TOUR!!!

PILE OF BOOKS

march 2014

Thanks to all of you who showed up at the gig last night and joined the musical journey through the land of love and its contradictions. thanks for coming and fill the room with your attention! thanks to listen til the very end to the stories i sang.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

BALASSO & BETULIUS

8. march 2014

such a women-power evening last night at balasso & betulius, the lovely tiny deli on gertrudstrasse in „kreis3“ in zurich. Dagny Gioulami and Lea Gottheil read their texts and poems and at least four generations of women gathered together to listen, celebrate and share a glass of wine! …juice and chocolate-fondue were provided for the young ones;-) THANK YOU DEAR SIL, you made it possible!!!!

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

A.PART

march 2014

What a night a part!!!! i mean really…the evening was just for ourselves at devi’s pearl. many women* showed up to listed to the gig and carefully listen to the lyrics…these are our stories to share and it is an honour to sing them out loud, make them heard. we all create such a great atmophere when we get together for a drink at mireille and fabienne’s. thanks for your support and for making the scene so diverse and colourful in zurich! come to the next gig: women*only!!!

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

INSIEME

february 2014

a great opportunity for me to sing and play in winterthur. to sing and listen to fabe vega again and live! meet new people, get new feedback about the performance and grow into beeing a singer and live performer! Thank you rafael, looking forward to be in winterthur again!

*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*:*

LA CATRINA

october 2013

dear all deer(s),how wonderful it has been to play and sing at „la catrina“! the evening started with rain. arriving on kurzgasse with a packed budget mobility-car (the day before i bought a rack the size of a table top fridge -half the car- to take along for the amp to sit) it felt like shiver or shelter. i could not tell. however. pat, annina and the sound-master made it easy for me to relax. they organized the stage and as i returned from the parking lot, all was ready for soundcheck. the venue was about empty. after a silent bird-dinner at the thai around the corner i realized that i had been a bad company for pat-roadie: it was the first time i had someone with me before the show!!! i could not talk. when the hypno-course will be through, pat will hypnotise me to help me overcome the anxiety attacks pre-gigs. though i got used to them and a „schnappsli“ helps just fine. as we returned from dinner, the place was packed!! loads of friends chatting outside the venue (it stopped raining in the meanwhile) and new faces, too. my concern: what the queeries will think when i will open the evening with „the facts about jimmy“ and jimmy will be a trans? well, it’s our lives, it’s our stories and it’s time to sing them so i did. s. colvin will understand the need of it and give permit. or be outraged. that night i sang two of my own songs in pubblic for the first time. i sang them out loud at „la catrina“. it made sense to me to dare. and i got lots of warmth from the audience to take with me on cold nights. THANK YOU!!!

5.9.2022

5.9.2022